Quick Q: Do smart pointers help replace raw pointers? -- StackOverflow

Quick A: Yes, smart pointers replace owning raw pointers, and you should prefer smart pointers in new code. Raw pointers and references are still appropriate to pass parameters down a stack.

Recently on SO:

C++ 11 Smart Pointer usage

I have a question about smart pointers in c++ 11. I've started to have a look at C++ 11 (I usualy program in c#) and read some thing about smart pointers. Now i have the question, does smart pointers completely replace the "old" style of pointers, should i always use them?

We don't normally link to pleas to

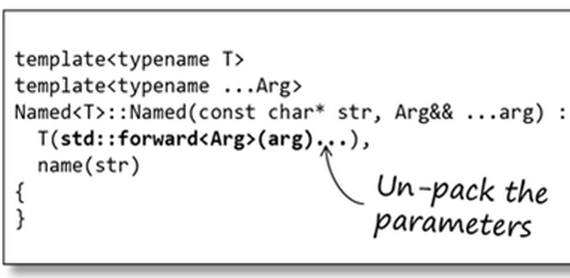

We don't normally link to pleas to  Recently on StickyBits, a nice primer on variadics:

Recently on StickyBits, a nice primer on variadics: Bulldozer00's appreciation for Alex Stepanov's introduction for Bjarne Stroustrup at CppCon. We already linked to the video last week -- but if you didn't watch it then, do yourself a favor and spend 6 minutes now getting your workweek off to a great start.

Bulldozer00's appreciation for Alex Stepanov's introduction for Bjarne Stroustrup at CppCon. We already linked to the video last week -- but if you didn't watch it then, do yourself a favor and spend 6 minutes now getting your workweek off to a great start. Freshly pressed from Andrzej:

Freshly pressed from Andrzej: One reasoned take on the various error reporting mechanisms in C++ and a policy for deciding when each is appropriate:

One reasoned take on the various error reporting mechanisms in C++ and a policy for deciding when each is appropriate: