2025-12 Mailing Available

The 2025-12 mailing of new standards papers is now available.

| WG21 Number | Title | Author | Document Date | Mailing Date | Previous Version | Subgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N5011 | Brno 2026 | Hana Dusíková | 2025-10-21 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| N5029 | WG21 2025-10 Kona Admin telecon minutes | Nina Ranns | 2025-10-27 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| N5031 | WG21 2025-11 Kona Minutes of Meeting | Nina Ranns | 2025-11-28 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| N5032 | Working Draft, Standard for Programming Language C++ | Thomas Köppe | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| N5033 | Editors' Report - Programming Languages - C++ | Thomas Köppe | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| P1317R2 | Remove return type deduction in std::apply | Aaryaman Sagar | 2025-11-13 | 2025-12 | P1317R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P1789R2 | Library Support for Expansion Statements | Alisdair Meredith | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | P1789R1 | LWG Library |

| P1789R3 | Library Support for Expansion Statements | Alisdair Meredith | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P1789R2 | LWG Library |

| P2243R0 | Language linkage for templates | S. Davis Herring | 2025-10-08 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P2728R10 | Unicode in the Library, Part 1: UTF Transcoding | Eddie Nolan | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | P2728R9 | SG9 Ranges,SG16 Unicode,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P2728R9 | Unicode in the Library, Part 1: UTF Transcoding | Eddie Nolan | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | P2728R8 | SG9 Ranges,SG16 Unicode,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3064R3 | How to Avoid OOTA Without Really Trying (Informational) | Paul E. McKenney | 2025-11-15 | 2025-12 | P3064R2 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism |

| P3097R1 | Contracts for C++: Virtual functions | Timur Doumler | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | P3097R0 | EWG Evolution |

| P3099R1 | Contracts for C++: User-defined diagnostic messages | Timur Doumler | 2025-10-19 | 2025-12 | P3099R0 | EWG Evolution |

| P3100R5 | Implicit contract assertions | Timur Doumler | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | P3100R4 | EWG Evolution |

| P3216R2 | views::slice | Hewill Kang | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3216R1 | SG9 Ranges,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library |

| P3220R2 | views::take_before | Hewill Kang | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3220R1 | SG9 Ranges,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library,Direction Group |

| P3371R5 | Fix C++26 by making the rank-1, rank-2, rank-k, and rank-2k updates consistent with the BLAS | Mark Hoemmen | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3371R4 | LWG Library |

| P3388R3 | When Do You Know connect Doesn't Throw? | Robert Leahy | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | P3388R2 | LWG Library |

| P3391R2 | constexpr std::format | Barry Revzin | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3391R1 | LWG Library |

| P3395R5 | Fix encoding issues and add a formatter for std::error_code | Victor Zverovich | 2025-10-19 | 2025-12 | P3395R4 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3400R2 | Controlling Contract-Assertion Properties | Joshua Berne | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | P3400R1 | SG21 Contracts,EWG Evolution |

| P3412R3 | String Interpolation | Bengt Gustafsson | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | P3412R2 | SG16 Unicode,EWG Evolution |

| P3424R1 | Define Delete With Throwing Exception Specification | Alisdair Meredith | 2025-10-26 | 2025-12 | P3424R0 | CWG Core |

| P3505R2 | Fix the default floating-point representation in std::format | Victor Zverovich | 2025-10-07 | 2025-12 | P3505R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3505R3 | Fix the default floating-point representation in std::format | Victor Zverovich | 2025-10-08 | 2025-12 | P3505R2 | LWG Library |

| P3612R1 | Harmonize proxy-reference operations (LWG 3638 and 4187) | Arthur O'Dwyer | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | P3612R0 | LWG Library |

| P3642R3 | Carry-less product: std::clmul | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-14 | 2025-12 | P3642R2 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3657R1 | A Grammar for Whitespace Characters | Alisdair Meredith | 2025-10-20 | 2025-12 | P3657R0 | CWG Core |

| P3657R2 | A Grammar for Whitespace Characters | Alisdair Meredith | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | P3657R1 | CWG Core |

| P3666R2 | Bit-precise integers | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | P3666R1 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3684R1 | Fix erroneous behaviour termination semantics for C++26 | Timur Doumler | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3684R0 | EWG Evolution,CWG Core |

| P3688R5 | ASCII character utilities | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | P3688R4 | SG16 Unicode |

| P3692R3 | How to Avoid OOTA Without Really Trying | Paul E. McKenney | 2025-11-13 | 2025-12 | P3692R2 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,EWG Evolution |

| P3695R3 | Deprecate implicit conversions between char8_t and char16_t or char32_t | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-20 | 2025-12 | P3695R2 | EWG Evolution |

| P3724R2 | Integer division | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | P3724R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3726R1 | Adjustments to Union Lifetime Rules | Barry Revzin | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | P3726R0 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution,CWG Core |

| P3735R1 | partial_sort_at_most, nth_element_at_most | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-17 | 2025-12 | P3735R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3737R2 | std::array is a wrapper for an array! | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-20 | 2025-12 | P3737R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3739R4 | Standard Library Hardening - using std::optional | Jarrad J Waterloo | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | P3739R3 | LWG Library |

| P3744R0 | Explicit Provenance APIs | Gonzalo Brito Gadeschi | 2025-12-02 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism | |

| P3751R0 | A gentle introduction to pointer authentication | Oliver Hunt | 2025-11-04 | 2025-12 | SG23 Safety and Security | |

| P3751R1 | A gentle introduction to pointer authentication | Oliver Hunt | 2025-11-04 | 2025-12 | P3751R0 | SG23 Safety and Security |

| P3763R1 | Remove redundant reserve_hint members from view classes | Hewill Kang | 2025-11-04 | 2025-12 | P3763R0 | SG9 Ranges,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library |

| P3772R1 | std::simd overloads for bit permutations | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-13 | 2025-12 | P3772R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3793R1 | Better shifting | Brian Bi | 2025-11-19 | 2025-12 | P3793R0 | SG6 Numerics |

| P3804R1 | Iterating on parallel_scheduler | Lucian Radu Teodorescu | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | P3804R0 | LWG Library |

| P3815R1 | Add scope_association concept to P3149 | Jessica Wong | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3815R0 | All of WG21 |

| P3816R1 | Hashing meta::info | Matt Cummins | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | P3816R0 | SG7 Reflection |

| P3824R2 | Static storage for braced initializers NBC examples | Jarrad J Waterloo | 2025-11-01 | 2025-12 | P3824R1 | SG23 Safety and Security,CWG Core |

| P3826R1 | Fix or Remove Sender Algorithm Customization | Eric Niebler | 2025-11-03 | 2025-12 | P3826R0 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library |

| P3826R2 | Fix or Remove Sender Algorithm Customization | Eric Niebler | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3826R1 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library |

| P3833R0 | std::unique_multilock | Ted Lyngmo | 2025-12-09 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWGI SG18: LEWG Incubator | |

| P3834R2 | Defaulting the Compound Assignment Operators | Matthew Taylor | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | P3834R1 | EWGI SG17: EWG Incubator |

| P3836R2 | Make optional<T&> trivially copyable (NB comment US 134-215) | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | P3836R1 | LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library |

| P3843R1 | Reconsider R0 of P3774 (Rename std::nontype) for C++26 | Jonathan Müller | 2025-11-17 | 2025-12 | P3843R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3843R2 | std::function_wrapper | Jonathan Müller | 2025-11-17 | 2025-12 | P3843R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3844R1 | Restore simd::vec broadcast from int | Matthias Kretz | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3844R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3844R2 | Restore simd::vec broadcast from int | Matthias Kretz | 2025-11-19 | 2025-12 | P3844R1 | LWG Library |

| P3847R0 | Lambdas capture left to right | S. Davis Herring | 2025-10-08 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3849R1 | SIS/TK611 considerations on Contract Assertions | Harald Achitz | 2025-10-12 | 2025-12 | P3849R0 | SG21 Contracts |

| P3852R0 | a (constexpr) utility to check if pointer points between two related pointers | Hana Dusíková | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3856R1 | New reflection metafunctions - is_structural_type (US NB comment 49) and is_destructurable_type | Jagrut Dave | 2025-11-01 | 2025-12 | P3856R0 | SG7 Reflection,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3856R2 | New reflection metafunctions - is_structural_type (US NB comment 49) and is_destructurable_type | Jagrut Dave | 2025-11-01 | 2025-12 | P3856R1 | SG7 Reflection,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3856R3 | New reflection metafunctions - is_structural_type (US NB comment 49) and is_destructurable_type | Jagrut Dave | 2025-11-01 | 2025-12 | P3856R2 | SG7 Reflection,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3858R1 | A Lifetime-Management Primitive for Trivially Relocatable Types | David Sankel | 2025-11-03 | 2025-12 | P3858R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3860R1 | Proposed Resolution for NB Comment GB13-309 atomic_ref is not convertible to atomic_ref | Hui Xie | 2025-11-04 | 2025-12 | P3860R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3868R1 | Allow #line before module declarations | Michael Spencer | 2025-10-30 | 2025-12 | P3868R0 | EWG Evolution |

| P3869R0 | Slides for P3666R1 Bit-precise integers | Jan Schultke | 2025-10-26 | 2025-12 | SG22 Compatibility | |

| P3869R1 | Slides for P3666R1 Bit-precise integers | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-02 | 2025-12 | P3869R0 | SG6 Numerics |

| P3876R0 | Extending <charconv> support to more character types | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-13 | 2025-12 | SG16 Unicode | |

| P3878R0 | C++26 Contracts are not a good fit for standard library hardening | Ville Voutilainen | 2025-10-23 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3878R1 | Standard library hardening should not use the 'observe' semantic | Ville Voutilainen | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3878R0 | LWG Library |

| P3880R0 | Make subspan aware of compile-time constants | Hewill Kang | 2025-11-11 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3881R0 | Forward-progress for all infinite loops | Simon Cooksey | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism | |

| P3883R0 | A Proposal for a Boolean Flip Operator in C++ | Muhammad Taaha | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | EWGI SG17: EWG Incubator | |

| P3884R0 | Slides for P3505R2 Fix the default floating-point representation in std::format | Victor Zverovich | 2025-10-19 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3885R0 | Add a formatter for std::error_category | Victor Zverovich | 2025-10-19 | 2025-12 | SG16 Unicode | |

| P3886R0 | Wording for AT1-057 | Michael Florian Hava | 2025-10-21 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3887R0 | Make when_all a Ronseal Algorithm | Robert Leahy | 2025-10-21 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3887R1 | Make when_all a Ronseal Algorithm | Robert Leahy | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3887R0 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3889R0 | A minimal solution for contracts, or, what is an MVP? | Harald Achitz | 2025-10-25 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3890R0 | Add description for parallel memory algorithms | Ruslan Arutyunyan | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | LWG Library | |

| P3891R0 | Improve readability of the C++ grammar by adding a syntax for groups and repetitions | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-22 | 2025-12 | CWG Core,LWG Library | |

| P3892R0 | unless_stop_requested | Robert Leahy | 2025-10-27 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3893R0 | The CppCon 2025 Talk on Contracts and CodeQL in Context | Mike Fairhurst | 2025-10-24 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3895R0 | Slides for P3724R1 - Integer division | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-03 | 2025-12 | SG6 Numerics | |

| P3896R0 | Design goals for a contract support facility | Andrzej Krzemieński | 2025-10-30 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3897R0 | Slides for P3776R1 - More trailing commas | Jan Schultke | 2025-10-31 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3898R0 | Slides for P3793R0 - Better shifting | Jan Schultke | 2025-11-02 | 2025-12 | SG6 Numerics | |

| P3899R0 | Clarify the behavior of floating-point overflow | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | SG6 Numerics | |

| P3902R0 | Against implicit conversions for indirect | Jonathan Coe | 2025-10-31 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3902R1 | Against implicit conversions for indirect | Jonathan Coe | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | P3902R0 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3902R2 | Against implicit conversions for indirect | Jonathan Coe | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | P3902R1 | LEWG Library Evolution |

| P3904R0 | When paths go WTF: making formatting lossless | Victor Zverovich | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | SG16 Unicode | |

| P3905R0 | C++ Standard Library Ready Issues to be moved in Kona, Nov. 2025 | Jonathan Wakely | 2025-10-30 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| P3906R0 | C++ Standard Library Immediate Issues to be moved in Kona, Nov. 2025 | Jonathan Wakely | 2025-11-28 | 2025-12 | All of WG21 | |

| P3907R0 | Waving more ::result_type goodbye | Zhihao Yuan | 2025-11-03 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3908R0 | constexpr from_chars<float> / to_chars<float> | Hana Dusíková | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3909R0 | Contracts should go into a White Paper - even at this late point | Ville Voutilainen | 2025-11-02 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3910R0 | Improving safety of C++26 contracts | Bengt Gustafsson | 2025-11-02 | 2025-12 | SG21 Contracts,EWG Evolution | |

| P3911R0 | RO 2-056 6.11.2 [basic.contract.eval] Make Contracts Reliably Non-Ignorable | Darius Neațu | 2025-12-10 | 2025-12 | SG21 Contracts,EWG Evolution | |

| P3912R0 | Design considerations for always-enforced contract assertions | Timur Doumler | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3913R0 | Optimize for std::optional in range adaptors | Steve Downey | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3913R1 | Optimize for std::optional in range adaptors | Steve Downey | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3913R0 | LWG Library |

| P3914R0 | Assorted NB comment resolutions for Kona 2025 | Tim Song | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | LWG Library | |

| P3915R0 | Responses to Trivial Relocation NB Comments | Pablo Halpern | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3917R0 | A Lifetime-Management Primitive for Trivially Relocatable Types (Presentation) | David Sankel | 2025-11-05 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3919R0 | Guaranteed-(quick-)enforced contracts | Ville Voutilainen | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3920R0 | Wording for NB comment resolution on trivial relocation | Louis Dionne | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,CWG Core,LWG Library | |

| P3921R0 | Core Language Working Group "ready" Issues for the November, 2025 meeting | Jens Maurer | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | CWG Core | |

| P3922R0 | Missing deduction guide from simd::mask to simd::vec | Matthias Kretz | 2025-11-06 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3922R1 | Missing deduction guide from simd::mask to simd::vec | Matthias Kretz | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | P3922R0 | LWG Library |

| P3923R0 | Additional NB comment resolutions for Kona 2025 | Tim Song | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | LWG Library | |

| P3924R0 | Fix inappropriate font choices for "declaration" | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | CWG Core | |

| P3925R0 | RO 3-292 29.10.8.3 [simd.comparison] Make `basic_simd` a Regular Type (with Boolean `operator==`) | Darius Neațu | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3926R0 | Slides: operator T& on indirect (in defense of US 77-140) | Zhihao Yuan | 2025-11-07 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3928R0 | static_sized_range | Hewill Kang | 2025-12-04 | 2025-12 | SG9 Ranges,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3929R0 | Fix safety hazard in std::function_ref | Jonathan Müller | 2025-11-17 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3931R0 | consteval all the non-allocating operator"" things | Hana Dusíková | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3933R0 | constexpr std::hive | Hana Dusíková | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3935R0 | Rebasing <cmath> on C23 | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-13 | 2025-12 | SG6 Numerics,SG22 Compatibility | |

| P3936R0 | Safer atomic_ref::address (FR-030-310) | Corentin Jabot | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3937R0 | Type Erasure Requirements For Future Trivial Relocation Design | Mingxin Wang | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3938R0 | Values of floating-point types | Jan Schultke | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | SG6 Numerics | |

| P3940R0 | Rename concept tags for C++26: sender_t to sender_tag | Arthur O'Dwyer | 2025-12-09 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3941R0 | Scheduler Affinity | Dietmar Kühl | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | SG1 Concurrency and Parallelism,LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3945R0 | Comments on D3933R0 (constexpr hive) | Matt Bentley | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution,LWG Library | |

| P3946R0 | Designing enforced assertions | Andrzej Krzemieński | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution | |

| P3947R0 | identifier_of Should Return std::string | Eddie Nolan | 2025-12-14 | 2025-12 | EWG Evolution,LEWG Library Evolution | |

| P3948R0 | constant_wrapper is the only tool needed for passing constant expressions | Matthias Kretz | 2025-12-15 | 2025-12 | LEWG Library Evolution |

aster Language Engine, Unique Constexpr Debugger, DAP Support, and Much More

aster Language Engine, Unique Constexpr Debugger, DAP Support, and Much More What a year I had! One more conference, one more trip report! I had the chance to go to Meeting C++ and give not just one but two talks!

What a year I had! One more conference, one more trip report! I had the chance to go to Meeting C++ and give not just one but two talks! C++11 gave us

C++11 gave us  The Budapest C++ Meetup was a great reminder of how strong and curious our local community is. Each talk approached the language from a different angle — Jonathan Müller from the perspective of performance, mine from design and type safety, and Marcell Juhász from security — yet all shared the same core message: understand what C++ gives you and use it wisely.

The Budapest C++ Meetup was a great reminder of how strong and curious our local community is. Each talk approached the language from a different angle — Jonathan Müller from the perspective of performance, mine from design and type safety, and Marcell Juhász from security — yet all shared the same core message: understand what C++ gives you and use it wisely. When working with legacy or rigid codebases, performance bottlenecks can emerge from designs you can’t easily change—like interfaces that force inefficient map access by index. This article explores how a simple

When working with legacy or rigid codebases, performance bottlenecks can emerge from designs you can’t easily change—like interfaces that force inefficient map access by index. This article explores how a simple  A missing

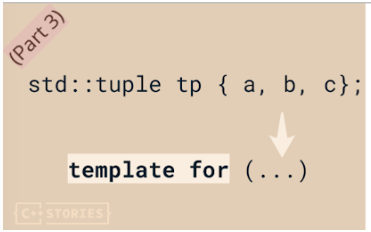

A missing  In this final part of the tuple-iteration mini-series, we move beyond C++20 and C++23 techniques to explore how C++26 finally brings first-class language support for compile-time iteration. With structured binding packs (P1061) and expansion statements (P1306), what once required clever template tricks can now be written in clean, expressive, modern C++.

In this final part of the tuple-iteration mini-series, we move beyond C++20 and C++23 techniques to explore how C++26 finally brings first-class language support for compile-time iteration. With structured binding packs (P1061) and expansion statements (P1306), what once required clever template tricks can now be written in clean, expressive, modern C++.