Flavours of Reflection -- Bernard Teo

Reflection is coming to C++26 and is arguably the most anticipated feature accepted into this version of the standard. With substantial implementation work already done in Clang and GCC, compile-time reflection in C++ is no longer theoretical — it’s right around the corner.

Flavours of Reflection: Comparing C++26 reflection with similar capabilities in other programming languages

by Bernard Teo

From the article:

Reflection is imminent. It is set to be part of C++26, and it is perhaps the most anticipated feature accepted into this version of the standard. Lots of implementation work has already been done for Clang and GCC — they pretty much already work (both are on Compiler Explorer), and it hopefully won’t be too long before they get merged into their respective compilers.

Many programming languages already provide some reflection capabilities, so some people may think that C++ is simply playing catch-up. However, C++’s reflection feature does differ in important ways. This blog post explores the existing reflection capabilities of Python, Java, C#, and Rust, comparing them with one another as well as with the flavour of reflection slated for C++26.

In the rest of this blog post, the knowledge of C++ fundamentals is assumed (but not for the other programming languages, where non-commonsensical code will be explained).

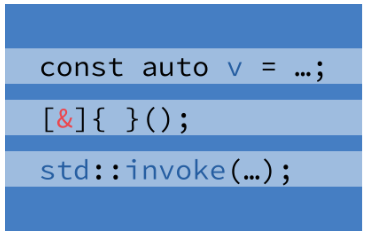

What do you do when the code for a variable initialization is complicated? Do you move it to another method or write inside the current scope? Bartlomiej Filipek presents a trick that allows computing a value for a variable, even a const variable, with a compact notation.

What do you do when the code for a variable initialization is complicated? Do you move it to another method or write inside the current scope? Bartlomiej Filipek presents a trick that allows computing a value for a variable, even a const variable, with a compact notation. Filtering items from a container is a common situation. Bartłomiej Filipek demonstrates various approaches from different versions of C++.

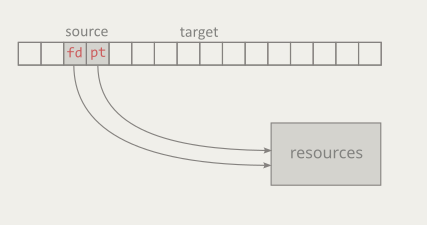

Filtering items from a container is a common situation. Bartłomiej Filipek demonstrates various approaches from different versions of C++. Value semantics is a way of structuring programs around what values mean, not where objects live, and C++ is explicitly designed to support this model. In a value-semantic design, objects are merely vehicles for communicating state, while identity, address, and physical representation are intentionally irrelevant.

Value semantics is a way of structuring programs around what values mean, not where objects live, and C++ is explicitly designed to support this model. In a value-semantic design, objects are merely vehicles for communicating state, while identity, address, and physical representation are intentionally irrelevant. In today's post, I like to touch on a controversial topic: singletons. While I think it is best to have a codebase without singletons, the real-world shows me that singletons are often part of codebases.

In today's post, I like to touch on a controversial topic: singletons. While I think it is best to have a codebase without singletons, the real-world shows me that singletons are often part of codebases.